(November 10, 2021) Like many veterans of the United States Armed Forces—especially those who served during times of war—Mason Fitch is often hesitant to discuss his military service. “I will sometimes talk about it when somebody asks,” says Fitch, a resident at Brickstone by St. John’s since 2014. “But I usually don’t bring it up.”

When Veterans Day comes along each year, people tend to ask about it a little bit more. Just this week, Fitch’s military service came up when he took his wife Ginn to an eye appointment. “The last time I was there, he asked me if I had served,” Fitch says of the ophthalmologist he and his wife have seen for years. When the doctor saw him again this week, he excitedly explained to Fitch that he had just watched a full-length video detailing his wartime contributions from the National World War II Museum.

When Veterans Day comes along each year, people tend to ask about it a little bit more. Just this week, Fitch’s military service came up when he took his wife Ginn to an eye appointment. “The last time I was there, he asked me if I had served,” Fitch says of the ophthalmologist he and his wife have seen for years. When the doctor saw him again this week, he excitedly explained to Fitch that he had just watched a full-length video detailing his wartime contributions from the National World War II Museum.

When the topic of Fitch’s service does come up, his story begins following his graduation from Brighton (N.Y.) High School in 1943. He took a job at Rochester Products, a division of General Motors, but knew he would soon be drafted. He discussed his plans with a co-worker, who pointed him in the direction of an I.Q. test needed to be voluntarily inducted into the Army Air Forces. Fitch jumped at the opportunity and passed the test, though over seven decades later, his clearest memory is of the test he failed that kept him from becoming an officer. “Still, in January of ’44 I got the call,” remembers Fitch. He then graduated from gunnery school and soon—following a brief foot injury—joined the very first group of B-29 gunners.

On Christmas Day 1944, he and his crew had completed their training and were in California with their bomber, unsure of where exactly they were headed. The next day they flew to Hawaii before making it to Kwajalein in the Marshall Islands. This was when the reality of what he and his squad were up against set in. “Our Colonel said ‘when you leave Kwajalein, you leave with loaded guns,’” an emotional Fitch remembers. “That was the first time I thought to myself that we were going to be shot at.”

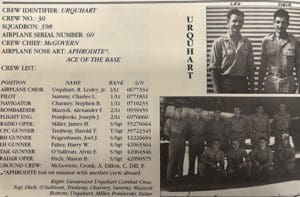

On New Year’s Day 1945, Fitch and his Urquhart Crew landed on Tinian—an island liberated from the Japanese just months before. North Field had been quickly constructed by the Seabees, and for a time served as the largest airport in the world once completed. It would be from this airfield that Fitch’s B-29 Superfortress and so many other allied bombers would stage missions across the Pacific throughout the remainder of the war.

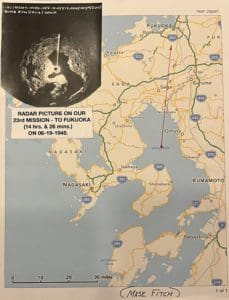

At 96-years old, Fitch still recalls the details from his service in World War II with the precision that made him the natural choice to be his squad’s radar operator. A few years ago when a group of veterans living at St. John’s Meadows and Brickstone got together to tell stories from their military careers, Fitch told a fascinating tale of one bombing mission over Japan that is believed to have led to the discovery of the Pacific Jet Stream. “I like to assume I was on the flight that discovered it, but I can’t say for certain,” he says today.

At 96-years old, Fitch still recalls the details from his service in World War II with the precision that made him the natural choice to be his squad’s radar operator. A few years ago when a group of veterans living at St. John’s Meadows and Brickstone got together to tell stories from their military careers, Fitch told a fascinating tale of one bombing mission over Japan that is believed to have led to the discovery of the Pacific Jet Stream. “I like to assume I was on the flight that discovered it, but I can’t say for certain,” he says today.

Imagine being a 19-year old onboard a B-29 returning from a bombing mission over Japan in 1945. “It was past midnight,” as Fitch tells it. “The tail gunner says ‘we’ve got fire in number 2.’ I look out the window and there is fire coming from the engine over the wing coming back so it lighted up our gunner’s compartment.” He then breaks down the position of each crew member, using a model B-29 that was given to him during a later visit to Japan. “Anyway, I’m sitting behind the star, which I never liked because I thought if I were the (enemy) fighter I’d pick on that star and shoot at it,” he continues. “We yelled to the engineer that we were on fire, and he explained that the fire was coming from the melting of the shaft. We were going to lose the propeller.”

The problem was that the propeller would eventually fly off, and it was unclear which direction the soon-to-be fiery projectile would travel. To one side was engine 1, with the cockpit on the other side. According to Fitch, the conversation amongst the crew went something like this:

Pilot: “I’m going to ditch (the plane).”

Master Sargent: “You’re not going to ditch. They’ll never find us out here. We’ve gotta go for Iwo, we’ve got enough gas.” (The famous battle for Iwo Jima had been won just two weeks prior to the mission, and was now in American control.)

Pilot: “But we’re going to lose the prop.”

Engineer: “Yup. We have to hope it goes up or down.”

The gunners and radar operator (Fitch) were instructed to put their parachutes on. Again, Fitch uses his model plane to show exactly where the escape hatch was where he would need to exit the plane, if he were even given the chance. The pilot put the plane in a dive and the entire crew hoped for the best. After the pilot pulled the bomber back out of the dive, the moment of truth arrived. “I heard the navigator say it (the propeller) flew (safely) over the tail,” he remembers. The pilot and crew made it to Iwo Jima and landed—one of four times Fitch remembers their bomber making an emergency landing short of Tinian after taking enemy gunfire.

Speaking with Fitch, one can understand why veterans like him are often unsure of revisiting these stories. He speaks of emergency landings and narrow escapes like the one that day. He also talks about those close to him who were lost. “I never talked about it before, never to Ginn or to our two girls,” he explains. “Not until the bomb group started having reunions.” Since moving to Brickstone, at times he has taken the opportunity to share stories with other residents, even hearing a hilarious tale about a pilot who had his leave cut short to deliver toilets to Australia.

It is estimated that less than 300,000 of the some 16 million Americans who served during World War II are still alive. Mason Fitch is one of those surviving veterans, and he is rightly proud of his service as a Junior Navigator. He also understands it took some luck along the way. “I’m the last one of our crew still around,” he says. “I’m a fortunate guy.”

It is estimated that less than 300,000 of the some 16 million Americans who served during World War II are still alive. Mason Fitch is one of those surviving veterans, and he is rightly proud of his service as a Junior Navigator. He also understands it took some luck along the way. “I’m the last one of our crew still around,” he says. “I’m a fortunate guy.”

Mason Fitch met his wife Ginn in a youth group at Asbury First United Methodist Church on East Avenue in Rochester, and they were married in 1949. After graduating from Syracuse University with help from the G.I. Bill and money earned from Ginn’s job working for a radiologist, they returned to Rochester. Mason spent 37 years as a senior design engineer with General Motors.